The Steward's House, our Landmark at the heart of Oxford

The Steward's House, our Landmark at the heart of Oxford

"...this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country."

The Oxford Union likes to consider itself at the vanguard of controversy. This was never more so than on 9 February 1933 when it held what is still considered to be one of its most notorious debates. It occurred in Hilary term, the second term starting in January, under the presidency of Frank Hardie. The House carried by 275 votes to 152 a motion ‘that in no circumstances would it fight for its King and Country’. The junior librarian, David Graham, had suggested the motion to the president, who said: ‘My dear chap, this is a very good motion but you can’t really suppose you will get anyone to speak in favour of it.’

Professor C. E. M. Joad, a well-known and dedicated pacifist, was to speak for the motion; Quintin Hogg (later Lord Hailsham) of All Souls would oppose it. A number of undergraduates wished to speak on both sides, and the debate was well-attended, though not packed. That the vote went in favour was thought to have been as much recognition of the skill with which Joad put his argument as any overwhelming conviction that what he said was right.

Nobody thought that the press would be interested: debates on pacifism and disarmament had been held before, and in 1927 an almost identical motion had passed in the Cambridge Union by 213 to 138 votes: ‘That lasting peace can only be secured by the people of England adopting an uncompromising attitude of pacifism’, which had aroused little comment.

The Standing Committee, Lent term 1933

The Standing Committee, Lent term 1933

However, a few days after the debate the Daily Telegraph carried a leader alleging that the vote was the product of ‘communist cells in the Colleges’. Next, the Daily Express ascribed the vote to ‘practical jokers, woozy-minded communists and sexual indeterminates’. The Times spoke of ‘children’s hour’, and correspondence poured in, full of disgust at the undergraduates’ behaviour.

Then, a group of life members led by Mr Randolph Churchill and including Quintin Hogg, decided to come up to the next meeting and support a proposal to expunge the motion from the Society’s records. Churchill called it an "abject, squalid, shameless avowal". It was this above all that gave the debate its notoriety, because when on March 2nd 1933 this second motion was moved, it was defeated by 750 to 138 votes.

This was nothing to do with Oxford students’ pacifist intentions, but a lot to do with their indignation at having the Union’s affairs interfered with by people no longer resident at the University. A thousand people packed the hall, determined to see that the motion was squashed. Randolph Churchill was loudly booed, escaping only narrowly from being debagged and thrown in the river.

It was inevitable, however, that those who so wished would see this vote as a triumphant upholding of the original motion. The Oxford Pledge, as it became known, took on a symbolic significance for many pacifists, and further debates were held, both in the United Kingdom and in America.

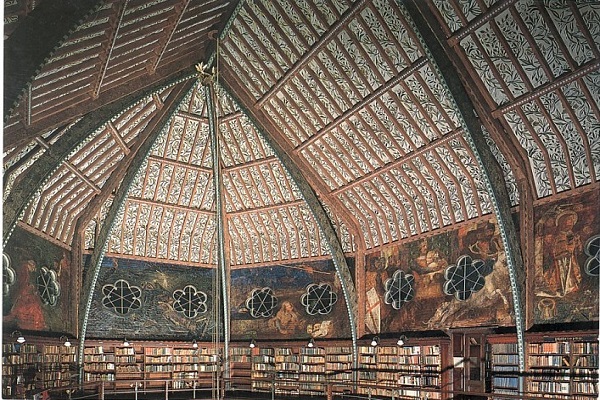

Murals and the ceiling inside the debate chamber

Much has been claimed to have resulted from the Union’s vote, from Mussolini’s involvement in the War to the Second World War itself. Other historians have argued that this is rather far-fetched, and it was not talked of in Berlin at the time – after all, Hitler had only been Chancellor for a few weeks at the time of the debate, and it was communist Russia, not Germany, who was generally thought of as the “enemy”.

Christopher Hollis, in his history of the Union (1964), suggests that the only tangible result was the admittance of women as members of the Union itself, though it took thirty years to achieve it. The reason for this was an immediate drop in membership – traditionally minded fathers, for instance, were not over-enthusiastic at the thought of paying for their sons to join an institution which had earned itself a reputation for controversy.

Severe financial problems resulted – the debate was estimated to have lost the Union £1,000 a year in revenue – the only solutions for which were to raise the subscription, which none of the undergraduates wanted, or to admit women, which the life members thought inconceivable. A long and bitter battle followed, which was not settled until 1963 (by which time the subscription had risen as well).

The motion that the House would not fight for King and Country has been debated in the Union on a number of occasions since 1933, and has generally been defeated, most resoundingly in 1983 by 417 to 187 votes.

The Oxford Union has continued to attract attention in the years since the King and Country debate. A televised debate in 1975 on Britain’s membership of the European Economic Community was watched by 11 million people and today it frequently hits the news due to its famed and sometimes unorthodox speakers, ranging from Marine le Pen to James Blunt.

A stay at the Steward’s House puts you at the heart of the debate. You may want to check which great orator, thinker, politician, pop star or sports personality would be sharing the building with you when you go and stay.

The Steward's House is available to book from £336. Click here to book your stay.

The living room inside the Steward's House

The living room inside the Steward's House